Scientific Programming and Computer Graphics

This article introduces the geometric transformation behind everyday tools like photo viewers and demonstrates how scripting in Scilab can replicate these operations.

PROGRAMMING

Rahul Mahajan

9/20/20252 min read

Scientific Programming and Computer Graphics

Perhaps the term Computer Graphics is incomplete without scientific programming. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that graphics programming can push computers to their limits when performed aggressively and in a systematic way. Almost all modern software are dispatched with a GUI, and the implementation of GUI's is made possible through a computer’s graphics processing capabilities. In fact, Computer-Aided Design exists because of the graphics that modern computers can handle. Image rendering and performing various operations on an image require processing vast amounts of data in a very short time-span to effectively visualize graphical entities on the display terminal.

For the user interface of any GUI-enabled computer program to become interactive, geometric transformation of graphical entities is necessary. Consider a simple application for viewing a photo in an image viewer on a computer. The minimum basic operations that the image viewer application supports are:

Zoom in/out

Pan

Rotate

Mirror

Without these basic operations, the image viewer program would be practically useless. When a user clicks the rotate command button on the screen, the photo or image rotates by the desired angle almost instantaneously.

Have you ever wondered how this works?

Well, we could dive much deeper to understand it. But as I mentioned earlier, these are introductory posts aimed at exploring the scope of scientific programming. Therefore, I won’t go into too much detail here. What I want you to do is open Scilab on your system and try something interesting related to image transformation.

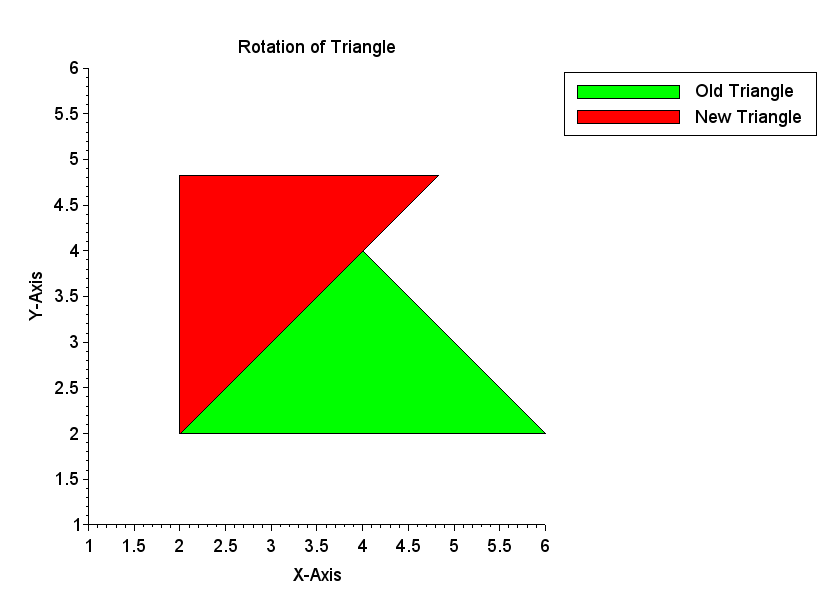

Consider a triangular image ABC with vertices A (2,2), B (6,2), and C (4,4). Suppose we want to rotate it about vertex A by 45 degrees counterclockwise.

In an image viewer program, we simply set the desired direction and angle of rotation and click the rotate button. The triangular image is then rotated instantaneously.

Now, open Scilab and run the following script.

//A triangle ABC with A (2,2) B(6,2) and C (4,4) is to be rotated about A by 45 deg ccw

clc

clear

ang=45

gcf().figure_name = "Rotation of Triangle by 45 deg"

OE=[2 6 4;2 2 4;1 1 1]

Tr=[1 0 -2;0 1 -2;0 0 1]

R=[cosd(ang) -sind(ang) 0;sind(ang) cosd(ang) 0;0 0 1]

bTr=[1 0 2;0 1 2;0 0 1]

Ct=bTr*R*Tr;

NE=Ct*OE

G=cat(2,OE,NE)

gca().axes_visible = ["on","on","on"]

title(" Rotation of Triangle","font_size",4)

xlabel(" X-Axis", "font_size",4)

ylabel(" Y-Axis", "font_size",4)

gca().font_size = 4

gca().isoview = "on"

gca().data_bounds = [min(G),min(G);max(G),max(G)]

xfpoly(OE(1,:),OE(2,:),3)

sleep(2000)

xfpoly(NE(1,:),NE(2,:),5)

legend("Old Triangle","New Triangle")

You’ll see both the original image and the rotated image. For clarity, both the old and new images are kept visible. In a photo viewer application, however, the old image disappears instantly.

Similar programs can be developed for other image operations that an image viewer supports. In fact, with the help of scientific programming and suitable front-end languages like Python, C#, or VB.NET, you can add custom options to an existing photo viewer or even design your own photo viewer application

Leave a reply

scientificprogramming.in

Explore scientific programming

Contact author

© 2025. All rights reserved.